Dino Discovery: NM Tech Geologist Helps Uncover New Findings about the Last Dinosaurs in New Mexico

Oct. 23, 2025

By Katie E. Ismael

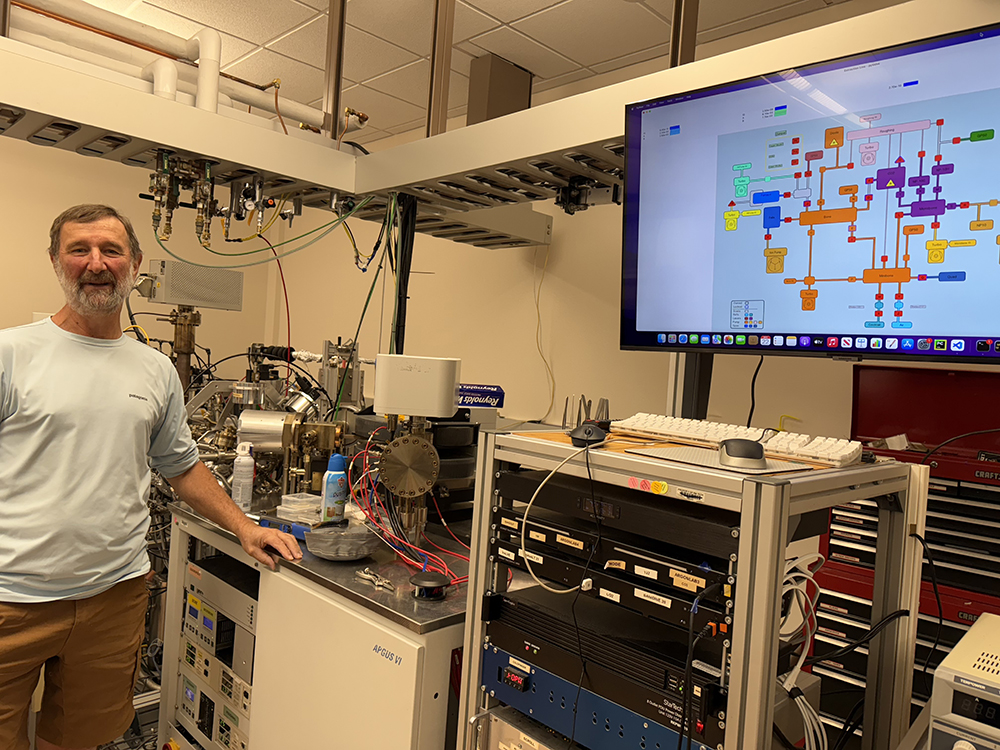

Matthew Heizler, a New Mexico Tech emeritus researcher and former director for the New Mexico Geochronology Research Laboratory at the New Mexico Bureau of Geology, in the Argon Geochronology Lab on campus where the dating of the samples occurred.

Very near the time of their ultimate extinction, dinosaurs were more diverse than scientists previously believed and actually a thriving species, according to new research published today in the journal Science.

Matthew Heizler, a New Mexico Tech emeritus researcher and former director for the New Mexico Geochronology Research Laboratory at the New Mexico Bureau of Geology, has developed an improved method for dating sedimentary rocks that do not contain obvious volcanic layers. This method led to new findings detailed in the paper “Late-surviving New Mexican dinosaurs illuminate high end-Cretaceous diversity and provinciality” authored by researchers from NM Tech, New Mexico State University, Baylor University, the University of Edinburgh and others around the world.

The team’s research took them to the San Juan Basin rocks of northwestern New Mexico, which holds one of the world’s richest records of the evolution of mammals that bloomed almost immediately after the worldwide extinction of 75 percent of all life on Earth. All dinosaurs, except for birds, which are their modern descendants, became extinct about 66 million years ago when an asteroid slammed into the Yucatan Peninsula in Mexico.

In the San Juan Basin is the Naashoibito member of the Kirtland Formation, a rock unit with a rich occurrence of dinosaur fossils that is now determined to be late Cretaceous and only slightly older than the age of the asteroid impact.

Heizler said that it is a prevailing notion that all non-avian dinosaurs may have been in decline, and ultimately more prone to extinction, millions of years before the final blow of the asteroid impact that wiped them out. This belief is primarily due to the lack of accurate age determination on dinosaur fossils from late Cretaceous rocks.

But Heizler said that improved geochronology methods developed at NM Tech show that, in fact, “the Naashoibito non-avian dinosaurs were diverse and thriving right up until the time of the impact.”

The dating method he helped pioneer called detrital sanidine builds upon more conventional detrital mineral dating methods, which have been around for decades. By specifically targeting and extracting the potassium feldspar sanidine derived from volcanoes and individually dating hundreds of them one at a time from a single sample, the age of sedimentary rocks can be estimated. Sanidine crystals occur in small quantities in many sedimentary rocks, and some of the sanidines in the Naashoibito appear to represent hidden volcanic material that was included in the Naashoibito when it was being deposited. The youngest crystals dated tell researchers that the sedimentary rock can be no older than these youngest crystals.

“In our current study, we dated 1,046 single sanidine grains and 10 of them gave ages between 66.4 to 66.8 million years old, telling us that the dinosaur fossils were no older than 66.4 million years, and thus several million years younger than previously thought,” said Heizler.

“In both the northern United States and New Mexico, and perhaps other locations in the world that are not well dated, we find very different and diverse dinosaur populations from region to region that are thriving right up to the time of their mass extinction,” he said.

Heizler’s research takes place in the Argon Geochronology Lab on the New Mexico Tech campus.

Read the news release from New Mexico State University.

Illustration of the last dinosaurs from southern North American, featuring the sauropod Alamosaurus sanjuanensis, from the Naashoibito Member in the San Juan Basin of northwestern New Mexico.

Rocks spanning the extinction of the dinosaurs in the San Juan Basin of northwestern New Mexico including numerous earliest Paleocene fossilized trees. The Cretaceous-Paleogene boundary is marked by transition from the grey latest Cretaceous Naashoibito Member and the tan earliest Paleocene Ojo Alamo Sandstone.

Daniel Peppe, Utanah Denetclaw, Anne Weil, & Blake Gorman collecting paleomagnetic samples from the latest Cretaceous Naashoibito Member in the De-Na-Zin Wilderness area of the San Juan Basin in northwestern New Mexico.

Caitlin Leslie collecting paleomagnetic samples from the lower Paleocene Nacimiento Formation in the San Juan Basin of northwestern New Mexico.